The Construction and Destruction of the Swamp Angel

Blog By Paul Hedden

By the middle of July, 1863 Union troops, under the command of Maj. Gen’l Quincy Gilmore, had consolidated their position on Folly Island, with a foot hold on Morris Island, and the troops made further attempts at establishing a more secure position on lower James Island by a feint aimed at Grimball’s landing via Battery Island. The overall strategic plan, however, remained: capturing Folly and all of Morris Island to enable a direct land based assault on Fort Sumter, and ultimately Charleston, itself.

To move this strategy forward, on the 15th of July orders were issued to determine a position in the marsh between Folly, Morris and James Island where a gun battery could be placed that would enable Union forces to bombard Charleston itself.

The following day orders were received by Colonel Edward W. Serrell of the New York Volunteer Engineer and his subordinate Lieut. N. M. Edwards to locate a site for the battery. The mission took them across the marsh from the batteries on Folly to the creek between Morris Island and Light-House Creek a distance of about half a mile. At this point there was a spot of hard ground just above, or below, high-water depending on the tide. This bit of occasionally dry land, from 25 to 80 feet long. and 15 to 18 feet wide,was almost at 90º to the enemy fire from Fort Sumter. This area of the marsh could only be be crossed by infantry at low tide, and with some difficulty. A man crossing on foot could possibly sink 2 to 8 inches if not more. A battery to be constructed at this point had to be entirely made of sand-bags, with platforms placed on a grillage (a framework of timber or steel for support on marshy or insecure ground).

The proposed surface for the gun, or guns, weighing no more than 10,000 pounds, would be drawn across the marsh on skids to slide over the mud. At this location it was estimated two thousand three hundred men would be needed to carry enough filled sand-bags, in one night, to make the battery and cover the magazine. Sixty more were estimated necessary to sled the platform across and put it in place on the grillage. Another 400 to 450 men would have to put the guns in position the next night. The required skid would require a surface, on the mud, of 90 to 100 square feet. Another 35 men would have to haul the magazine across this muddy and treacherous path and set it up. Or approximately 4800 men total. The possible placement of the battery at this site came with two additional difficulties: a small creek, about 9 feet wide was in the way, with only a narrow ‘bridge’ of three logs to cross over, and the work had to be completed in daylight, in sight of enemy guns.

Subsequent examinations of various sites were sought down stream between Light-House Creek and Vincent’s Creek; on the morning of the 30th soundings were made with an iron rod 30 feet long, and ¾ inch in diameter at a site located midway between Morris and James Islands, 7,000 yards from the lower end of Charleston City. The chosen location was named the Marsh Battery, although it is generally known as the Swamp Angel, a name conferred upon it by the soldiers.

In these marshes, back from the harder edges of the creeks, the mud is generally about 20 feet deep. It is so soft that the weight of the sounding iron will carry it down 8 or 10 feet, and a man can push it the remainder of the distance to the bottom which has the feel of hard sand. At the selected location the surface of the mud, though covered by a growth of very coarse grass 4 or 5 feet high, didn’t provide secure footing, nor substantial resistance to anything sinking through it; at high tide water covered the surface of the mud. The edges of the small creeks bisecting the marsh are hard, and frequently filled with oysters and oyster shells; yet a few feet from the water the marsh again becomes very soft, again not affording a stable foothold. The gelatinous qualities of the marsh can be demonstrated by the fact two men on a plank resting on the surface can shake the surrounding surface of the marsh by bouncing themselves about. The vibrations extend over many hundreds of square yards, as if they were on jelly.

Knowing this the construction engineers formed a general idea of the kind of structure to be built and made preparations to obtain the necessary material, and provide the means of getting it placed as near to the city of Charleston as practicable on a stream just southeasterly from Light-House Creek. During the time preceding the final approval of this site and the commencement of the work at this location, a causeway leading to Black Island was being built. This demanded the use of large timber in great quantities. Working parties were sent to Folly Island to cut and prepare the lumber and bring it forward ready for use. It was determined that the proposed parapet must be made of sandbags. A point was chosen near the engineers camp: troops, and working parties worked day and night filling bags and hiding them from the enemy’s view under the over of bushes and ridges. The platform used as a base for the parapet was loaded with sand-bags, piled in regular layers, until a load equal to 400 pounds/sq ft was reached; and although the mud was so soft that the sandbags could not be carried by the men without sinking, except by walking on boards, the column of bags on the platform remained standing, and, after twenty-four hours, showed no signs of settlement.

Then more sand-bags were piled upon the column, reaching a height of 7 feet, with a weight of about 650 pounds to the square foot. This resulted in a tilt to one side. This was thought to be caused by the soldiers “tramping about near the corner that went down first.”

After a return to a state of equilibrium additional bags were piled upon the column, until a force of about 900 pounds/sq ft on the platform was reached. The platform suddenly tipped, throwing sand-bags into the marsh., burying many on the top tier into the mud. The platform sank only about a foot at one corner. This trial showed the sustaining strength of the marsh was equivalent to over 600 pounds to the square foot when the load was uniformly distributed. The ultimate sustaining strength was not ascertained.

Now, the average weight of a Union soldier was calculated to be 143¼ pounds [see The Men In The Union and Confederate Armies, at http://civilwarhome.com/themen.html]. And a man weighing150 pounds presented something like a force of 500 or 550 pounds/sq ft. when walking. So if a battery was to be built, so long as the guns were not fired, the forces would essentially be static. But guns, to be offensively useful, must be fired, and to fire them while floating, as it were, on the surface of the mud would produce vibrations. How far these vibrations would affect the stability of any structure so situated was still undetermined.

This conundrum indicated a free-floating battery would not be able to sustain a long-term bombardment of Charleston; a battery anchored to the floor of the marsh was necessary. If a pile-driver was to be employed to make a foundation, provision would have to be made to hide it during the day and work it at night, or it would be destroyed by the enemy’s fire. A machine as large as a pile-driver could not be used. The time required to set it up and take it down during the short nights of summer would consume too much of the few hours there were left to work in with any degree of security. For this reason a device was improvised where, a number of men forced the piles into the mud until the point reached hard bottom. It was then driven into the sand securely by heavy wooden mauls.

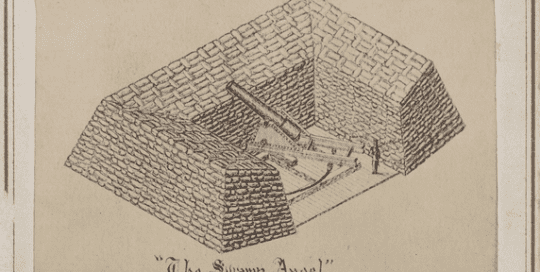

On the morning of August 2nd, General Gilmore had approved the plan for construction of the battery. Simply, the general theory of the structure is this: The marsh, being capable of sustaining a given weight, and no more, to the square foot, and it being necessary to have a certain height and thickness of parapet, thought best to be made of sand-bags, an equation was worked out to determine the size of the foundation and the weight to be supported. The foundation had to be large enough to support the necessary weight without sinking.

The foundation is a grillage, made of pine logs, crossed and bolted together. The center of gravity of the gun battery will be independent of the system upon which the gun rests, which is placed in the center of the platform. The timber work on which the gun rests in the center of the battery is independent of the parapet or its foundation. The foundation of the parapet receives a much greater load to the square foot than the gun-deck, and gun-deck’s weight elevates the entire structure on which the gun rests, not allowing the gun-deck to settle. i.e. If the battery should sink in the mud, the gun would be left standing on its own foundation, while the displacement would elevate the surface of the surrounding marsh, and tend, so far as it acted through or under the sheet piling which surrounds the gun platform, to elevate it. Thus, if the battery sank on its foundation, sand-bags could be piled upon it indefinitely, while the up heaved mud would form a glacis around it, and the gun would remain in one constant position.

The battery is in a rectangular shape formed by sheet piling. On this was laid a thick stratum of grass which was thoroughly tamped down; then followed two thicknesses of tarpaulin, on which was placed about 15 inches of well-rammed sand. Over this was laid three thicknesses of 3-inch pine plank. The interstices between the grillage logs are filled with sand, and around the logs are piled broken sandbags as a ramp, to give additional weight to keep it from rising unequally if the battery should sink.

A corduroy road (a road formed of logs and planks transversely placed in the mud), was built from the site of the battery, leading from its left side to the edge of the river. The gun and gun carriage, and the timber work forming the gun platform, were taken over this road from boats brought to the landing place, at the end, at high water.

During construction, all materials were carried by boats; many of the workers went to the job and returned this way. This was replaced with a plank walk built between Black Island and the Marsh Battery. After the night of the 12th of August most of the work-men were marched over the walk.. A platform was built on which a reserve covering party were stationed. Also, to secure the working parties against surprise, picket-boats were kept in the stream leading to James Island and Charleston Harbor, along with two naval boats with bow howitzers. Supplementing these precautions a boom of pine logs was put across the river to obstruct passage of boats that might attempt to come up from Charleston Harbor.

The building the Marsh Battery consumed the following labor and materials:

Thirteen thousand sandbags;

123 pieces, 15 to 18 inch diameter yellow pine timber 45 to 55 feet long,

5000 feet 1 inch boards ; 8 pallets 18 by 28 each;

9,156 feet 3 inch pine plank;

300 pounds 7-inch, and 300 pounds 4-inch spikes and nails ;

600 pounds round and square iron; 75 fathoms 3-inch rope.

These quantities do not include the material or labor employed in the bridges and plank walk across the marsh, and the boom, or the road and pier at the old engineer camp.

The gun to be fired from the swamp angel battery was an 8-inch Parrott Seacoast Rifle, invented by Captain Robert Parker Parrott, a graduate of West Point. He created the first Parrott rifle (and corresponding projectile) in 1860 and patented it in 1861. The Swamp Angel gun was manufactured the same year.

The gun was an iron tube 162 inches long. (Conflicting sources claim the gun to be 146 inches); weighing 16,500 lbs; with a bore of 8 inches. When it had a standard powder charge weighing 16 pounds to fire a 150 lb. Bolt (a solid projectile that included no explosive charge and had a cylindrical or spherical shape). It had an effective range of 8000 yards (just over 4½ miles at a constant elevation of 31º 30´.

The bombardment of the city of Charleston began from the Marsh Battery the night of August 21st. The Parrott rifle burst at the 36th round. No military results of great value were ever expected from this firing. which caused little damage and few casualties. Its primary purpose was to begin the bombardment of Charleston and a reign of terror on the civilian population.

Remains of the Swamp Angel Battery are still to be seen between Morris and Black Island. The Swamp Angel gun is now displayed in Cadwallader Park in Trenton, N.J.